Dale Going is a poet and book artist living in Mill Valley, California. As the proprietor of Em Press, she prints letterpress editions of poetry by innovative women writers. Her first play, Out of the Q, a collaged comedy about the book, recently premiered at the Berkeley Arts Center.

Denise Newman's book of poems Human Forest will be out next January by Apogee Press, and her translation of The Painted Room by the Danish poet Inger Christensen will be out in the fall by Harvill Press, UK.

Working Notes

by Dale Going

The artisan production of handmade books has its limitations and its allures for the poet. Compared to the potential for readership via the web or a trade book, audience is minimal. These books are made as unique objects or small editions, often regarded and valued as art objects over text, displayed in exhibition cases where typically they are opened to a single spread illustrating the graphic qualities of the book at the expense of what is, for the poet, a book’s primary activity: it is meant to be read. The diminished scale of readership is perhaps not too great a regret for the poet, whose realistic expectations in the realm of audience are not so large to begin with as those of artists in some other media. And since reading is a solo sport, the quality of the experience for the audience is in no way diminished by the size of the edition.

In fact, the quality of the reading experience can be hugely enhanced by the visual, textural articulation of the handmade book itself, by its materiality. In an artist’s book, the elements that make up a book — the papers, structure, typography, illustrations, binding, etc. — are a part of the poetics. The reading possibilities are multiplied.

The San Francisco Bay Area is a center of experimental practice for both poetry and book arts. In co-curating, with Jaime Robles, an exhibition in June 2000 at the Berkeley Arts Center called Livres de poètes (femme), I’ve had the pleasure of reading, handling, looking at — experiencing — about a hundred such handmade books by poet/book artists whose work balances on the textual/visual cusp. I talked with six artists whose work covers a range of methods, techniques, and intentions. I wanted to know why they had come to be so attracted by the materiality of books and how they worked with the interplay of text and image, the two – dimensionality of the page and the three-dimensionality of the book object, the various kinds of composition and construction involved in making poems and making books.

Note

Livres de poètes is a term coined by Eléna Rivera, after Livres d’artistes, to describe the work of poets whose poetics include the materiality of making books.

Contacts

Dale Going dalegoing@aol.com. Her work can be found online at http://sanfrancisco.citysearch.com/E/F/SFOCA/0000/12/66/ and at http://www.kelseyst.com/view.htm

Lisa Kokin lkokin@aol.com, is represented by Catharine Clark Gallery, http://www.cclarkgallery.com

Emily McVarish 105617.2755@compuserve.com

Denise Newman denisenewman@juno.com. Her work can be found online at and at http://www.apogeepress.com/HumanForest.html

Eléna Rivera erivera1@idtnet. Her work can be found online at http://www.kelseyst.com/unknown.htm.

Jaime Robles jrobles@best.com

Meredith Stricker wavestudio@redshift.com

The Book Arts Web http://www.philobiblon.com. Book arts list, gallery, great links to organizations, centers, education, supplies, publications, book artists and press pages.

Lisa Kokin

I don’t just make books; I also make sculpture and installation art. But the books are really my big love, because they’re intimate and personal and interactive in a way the other work isn’t as much. I really like to write even though I don’t consider myself a writer; I like puns, the multiple meanings and associations of words, how words sound. I’m doing word assemblage. I make assemblage sculpture and that’s what I do with words. I put unlikely words together and that’s how I create other stories.

I’ve been making books since 1991. My primary source for art supplies is the flea market; I’m intrigued by other people’s detritus. At some point I started using other people’s cast off words. I would take parts of books and cut them up and juxtapose them with parts of other books, such as a sex manual with a hunting guide. Writing in this way, I came up with lots of surprises that I wouldn’t necessarily have come up with on my own.

The themes of my work have to do with sexuality, history, Jewish identity, challenging the status quo, class, economics. I try to take these serious issues with as much levity as I can. I hate work that’s didactic, but I also always want to take jabs at the system, the inhuman forms of existence that we all are forced to live under.

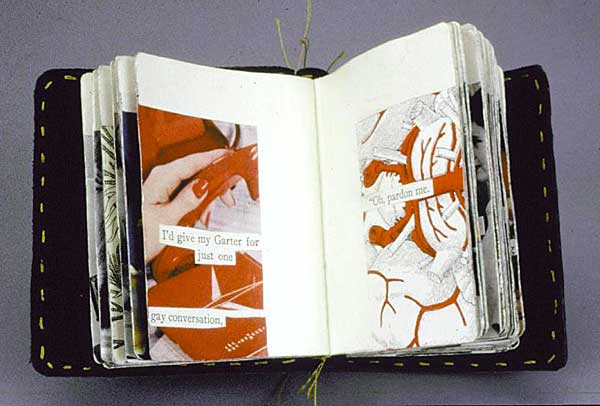

There are a number of ways I work. One is to delete parts of a text and leave words in that form a completely different text, one that usually subverts the original. That’s the case with That Two-Edged Bliss, which came from a book called, When Knighthood Was in Flower. I delete text in many different ways: covering it with strips of money, cutting it with an exacto-knife, sewing it out, taping it out; I use all sorts of methods to hide or partially hide original text and let other words come out.

That Two-Edged Bliss is one of a number of pieces that I’ve done about being bisexual and how a lot of people have a difficult time with that because it’s not one or the other; it’s both/and not either/or. I got this weird old book and started picking it apart, taking out large amounts of text and leaving certain words. I found images from various sources — old encyclopedias, women’s magazines from the 1950’s, sewing books, religious and historical photographs — and paired them with the pages in an intuitive way. I just gravitate to certain images. I pair them if my gut tells me to; I try to go with that without thinking too much about it.

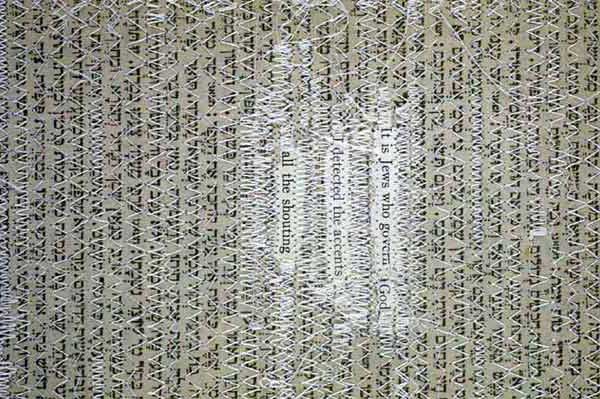

Another way I work is to cut out phrases from one book, or sometimes more than one. In the case of Selections from Mein Kampf, I had a copy from the flea market. I didn’t know what I was going to do with it but I knew I had to have it, because how often do you come across a copy of Mein Kampf from the 1940’s? It sat around in my studio for several years emitting toxic rays. One day I just had it cut up into several pieces. I ended up making four books out of it. In one, I burnt out text; in another, I covered text with strips of Hebrew writing; in a third, I used a tape transfer method to obliterate parts of the text. On the one shown here, I tore out phrases from the original and reassembled them to make poems in which Hitler expresses remorse and contradictory feelings about what he has done. I sewed them together onto pieces of a Hebrew prayer book that I’d found in a second hand store in a state of complete disrepair — I felt guilty about using it but it was already falling apart.

Sewing plays a very important role in my work. My background is in textiles. My parents were upholsterers; I grew up around fabric and thread and needles and learned how to sew at an early age. In my sculpture I use sewing as a way of drawing, of creating line. In books, it’s a way of integrating text from different sources. I find zig-zag a great way of making the transition between different kinds of paper; it makes the page more of an integrated whole rather than one paper stuck on another. Plus, I really like sewing things that are not normally sewn; I sew everything from paper to wood to metal. I like its associations with domestic, traditionally women’s work and craft and using that in my art.

Emily McVarish

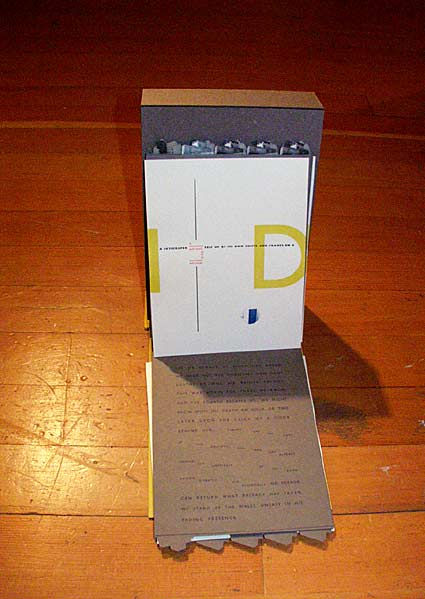

I’ve been really interested in the three-dimensional and mechanical aspects of reading and poetics. Conventional books pretty much have one way they work mechanically; they do have a third dimension, but the two-dimensional page is more central. Most of the work I’ve done has been sculptural, oftentimes with more than one mechanical feature. Some of these pieces emphasize one feature of a book, say the turning of a page as a repetitive motion, while limiting other graphic possibilities. There’s an exaggeration of the object status of the book. Using found objects in the sculptures has given me so much to go on conceptually and in terms of design incidents; there was an immediate dialogue with those objects that helped me to figure out how to structure a book. With found objects, their material history has been immediately apparent. The interplay between that and the text has been accessible to me and the viewer. I’m now trying to work with conventional forms or formats, both graphical and structural, as being in some way found — a shift from an actual old object to something slightly more abstract — but trying to take on the convention in the same critical (in the sense of exploratory) way.

I think the sculptures were my way into books; I was hesitant to take on the conventional book format and was more interested in figuring out what about that format drew me, by playing out different aspects of that. Now that I’m figuring out what those single factors were, I’m getting up the courage to face the conventional book.

I have also made catalogs that accompanied and documented exhibitions of the sculptures. They contain all the texts that were incorporated in the sculptures, yet have their own being. The emphasis of the show, an ephemeral event, was on fragmentation and dissemination. Say I wrote a text and paired it with six linotype drawers. That text might then be divided into six parts; each drawer would become one chapter in the text. The exhibition was the event where you would see the whole thing, but I would sell the six pieces separately: the ultimate fate of those objects was to get pulled off in bits. The catalog was a concession of a not quite admitted desire on my part for the text to have some endurance; it grouped and kept it whole; in that way it was a lot more like a traditional book. At that point, the traditional book form couldn’t satisfy the more radical interest to have things more temporary, more contingent on context, that the shows provided for me. It’s only now that I’m trying to figure out how a book might less have that pretense to being permanent and whole.

The texts are almost all the product of the process of cutting up existing texts and recomposing them. It starts with choosing a few books that interest me and trying to scan, not really read, the texts, like an airplane going over a landscape. I cut them out and have a whole system of arranging those bits. If I already know there’s going to be a theme that I’m writing about, I might arrange according to that theme; but usually the arrangement’s grammatical. This method of composition is a way of creating a dialogue between me and these bits of text rather than trying to find something within my head without that kind of prompt. It’s definitely influenced by surrealist and automatic writing and other kinds of rule-based and chance composition, but I’m not that systematic; it’s not about demonstrating something by pure experiment, it’s just a way for me to write. The bits that I’ve cut out have gotten smaller and smaller; basically, they’re single words now, whereas when I started out, they would be whole sentences, citations of whole thoughts. There has been a real continuity between that process of writing and the next step of setting type — and the found objects, which would determine everything from the structure of the piece to the size of the edition. I used to work with multiple determinations: for every step, every decision, I would make sure I had material determinations to work with. Now that’s changing somewhat. I don’t necessarily work with type and I’m doing less found object work. But the texts themselves still come out of a material, concrete, exchange with words.

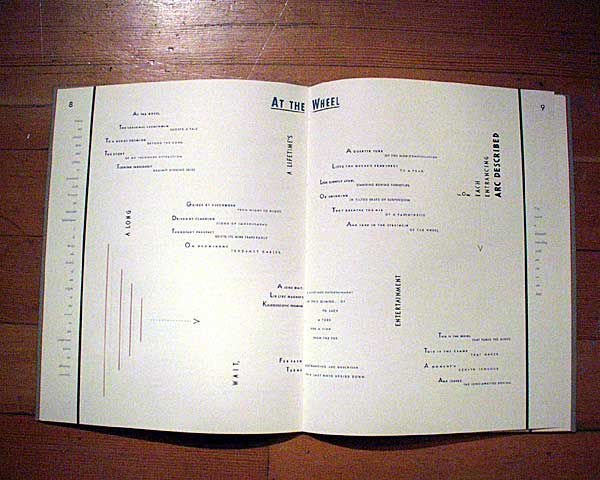

At the wheel is part of a series of texts, included in the exhibition and catalog Wards of Obsolescence, that I wrote under the influence of Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project. The Arcades Project is the hidden center of Benjamin’s entire oeuvre, a thousand pages of notes, fragments, quotations, citations, about the arcades of Paris as the perfect 19th century construct. The arcades were a favorite image for surrealist writers; they held a ghost or aquarium feeling, because they were already dead by the beginning of the twentieth century; Benjamin saw them as greenhouses for 19th century dream images. This year, The Arcades Project has finally been translated into English; I had for years had the French translation. It’s been for me an infinitely inspiring source, including the whole series of texts that At the wheel came from. I tried to take Benjamin literally: he was saying we could make a critical history out of the stuff itself. I thought I would take old stuff and make the books out of that, using objects the way he regards them, as being revelatory about the implications of the history that they carry. I took certain images as evocations of modernity. At the wheel is the image of the ferris wheel — waiting in line, getting on the wheel, entertainment — used to discuss the Benjaminian idea of popular culture presenting pseudo-satisfactions of what are essentially utopian dreams. It’s about waiting for technology to give us what can only come from social change.

The presence of the human figure in the Wards of Obsolescence series was on the level of society; I had been thinking about the writing of history. Then I thought, what happens where existential and historical time meet? A quote by Siegfried Kracauer, “The flight of images is the flight from the revolution and death,” was the beginning of Lives and Property for me. Kracauer was saying that the onslaught of the visual in modern society not only keeps us from seeing real economic conditions but also has an individual existential influence of keeping us from contemplating our own death. Where do the social and societal and political intersect with individual existence and the things — including death — that determine and define individual existence? Lives and Property is an exploration of that intersection. Death is in the middle of that text; the whole piece is like a tombstone; everything about it is dark and dense, gray and closed onto itself. The title refers to the way those things are counted and named on an historical level: the damage of major conflicts, for example, is counted in terms of lives and property. The piece looks at the relationship between existence viewed from that historical point-of-view and existence viewed from the first person point-of-view back up at history.